On October 20, Francesca Mani was called to the counselor’s office at her New Jersey high school. A 14-year-old sophomore and a competitive fencer, Francesca wasn’t one for getting in trouble. That day, a rumor had been circulating the halls: over the summer, boys in the school had used artificial intelligence to create sexually explicit and even pornographic photos of some of their classmates. She learned that she was one of more than 30 girls who may have been victimized. (In an email, the school claimed “far fewer” than 30 students were affected.)

Francesca didn’t see the photo of herself that day. And she still doesn’t intend to. Instead, she’s put all her energy into ensuring that no one else is targeted this way.

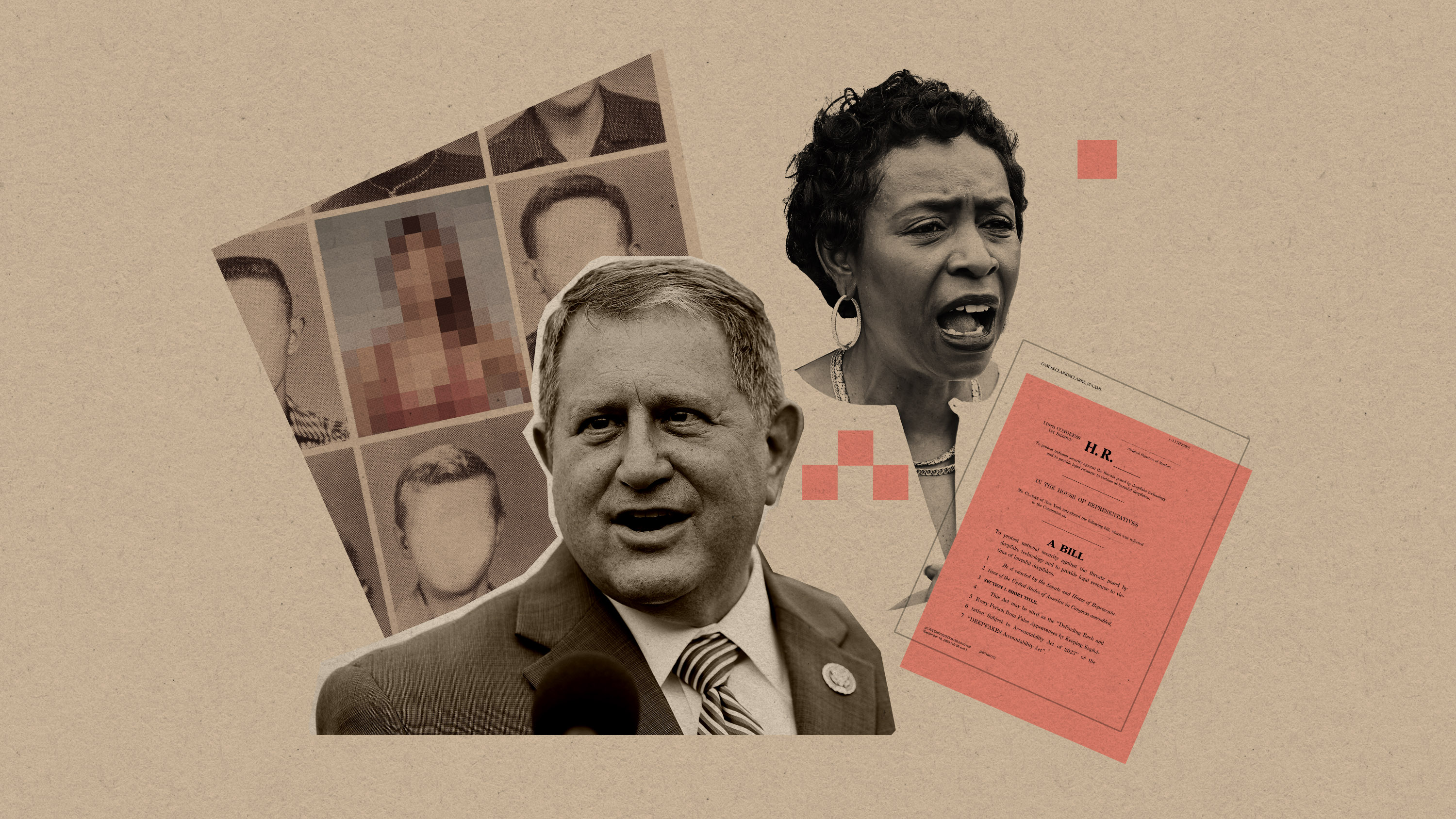

Within 24 hours of learning about the photos, Francesca was writing letters to four area lawmakers, sharing her story and asking them to take action. Three of them quickly responded: US Representative Joe Morelle of New York, US Representative Tom Kean Jr. of New Jersey, and New Jersey state senator Jon Bramnick. In the past few weeks, her advocacy has already fueled new legislative momentum to regulate nonconsensual deepfake pornography in the US.

This story is only available to subscribers.

Don’t settle for half the story.

Get paywall-free access to technology news for the here and now.

Subscribe now

Already a subscriber?

Sign in

“I just realized that day [that] I need to speak out, because I really think this isn’t okay,” Francesca told me in a phone call this week. “This is such a new technology that people don’t really know about and don’t really know how to protect themselves against.” Over the past few weeks, in addition to celebrating her 15th birthday, Francesca has also launched a new website that offers resources to other victims of deepfake pornography.

Studies from 2019 and 2021 show that deepfakes—which are images convincingly manipulated by artificial intelligence, often by swapping in faces or voices from different pieces of media—are primarily used for pornography, overwhelmingly without the consent of those who appear in the images. Beyond consent, deepfakes have sparked serious concerns about people’s privacy online.

As AI tools have continued to proliferate and become more popular over the last year, so has deepfake pornography and sexual harassment in the form of AI-generated imagery. In September, for instance, an estimated 20 young girls in Spain were sent naked images of themselves after AI was used to strip their clothes in photos. And in December, one of my colleagues, reporter Melissa Heikkilä, showed how the viral generative-AI app Lensa created sexualized renderings of her without her consent—a stark contrast to the images it produced of our male colleagues.

Efforts from members of Congress to clamp down on deepfake pornography are not entirely new. In 2019 and 2021, Representative Yvette Clarke introduced the DEEPFAKES Accountability Act, which requires creators of deepfakes to watermark their content. And in December 2022, Representative Morelle, who is now working closely with Francesca, introduced the Preventing Deepfakes of Intimate Images Act. His bill focuses on criminalizing the creation and distribution of pornographic deepfakes without the consent of the person whose image is used. Both efforts, which didn’t have bipartisan support, stalled in the past.

But recently, the issue has reached a “tipping point,” says Hany Farid, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, because AI has grown much more sophisticated, making the potential for harm much more serious. “The threat vector has changed dramatically,” says Farid. Creating a convincing deepfake five years ago required hundreds of images, he says, which meant those at greatest risk for being targeted were celebrities and famous people with lots of publicly accessible photos. But now, deepfakes can be created with just one image.

Farid says, “We’ve just given high school boys the mother of all nuclear weapons for them, which is to be able to create porn with [a single image] of whoever they want. And of course, they’re doing it.”

Clarke and Morelle, both Democrats from New York, have reintroduced their bills this year. Morelle’s now has 18 cosponsors from both parties, four of whom joined after the incident involving Francesca came to light—which indicates there could be real legislative momentum to get the bill passed. Then just this week, Representative Kean, one of the cosponsors of Morelle’s bill, released a related proposal intended to push forward AI-labeling efforts—in part in response to Francesca’s appeals.

AI regulation in the US is tricky business, even though interest in taking action has reached new heights (and some states are moving forward with their own legislative attempts). Proposals to regulate deepfakes often include measures to label and detect AI-generated content and moderate child sexual abuse material on platforms. This raises thorny policy issues and First Amendment concerns.

Morelle, though, thinks his bill has found an “elegant” solution that skirts some of those issues by focusing specifically on creators and distributors—developing an avenue for civil and criminal charges, and designating the creation and sharing of nonconsensual pornographic deepfakes as a federal crime. The bill “really puts the liability and the exposure on the person who will post something without the consent of the person who’s in the image and or video,” says Morelle. The bill is under consideration in the House Judiciary Committee, and Morelle’s office plans to push hard for passage in January. If it moves through committee, it will then go to a vote on the House floor.

Farid says that Morelle’s bill is a good first step at toward awareness and accountability, but in the long run, the problem will need to be tackled upstream with the websites, services, credit card companies, and internet service providers that are “profiting” from nonconsensual deepfake porn.

But in the meantime, the dearth of regulation and legal precedent on deepfake pornography means that victims like Francesca have little to no recourse. Police in New Jersey told Bramnick that the incident would likely amount to nothing more than a “cyber-type harassment claim,” rather than a more serious crime like child pornography. After Bramnick got in touch with Francesca, he joined on as a cosponsor of a bill in New Jersey that would institute civil and criminal penalties for nonconsensual deepfake pornography at the state level.

The sense of powerlessness is precisely what Francesca is hoping to change. She and her mom, Dorota Mani, are planning to head to Washington, DC, in the next few weeks to speak with members of Congress to bring more attention to the issue and urge them to pass Morelle’s bill.

“We should put laws in place, like, immediately—so when that happens to you, you have a law to protect you,” Francesca told me. “I didn’t really have a law to protect me.”

Update: This story has been updated to clarify how many students the school claims were affected by the incident.