How to stop a state from sinking

Louisiana’s southwestern coastline faces some of the most severe climate predictions in the US. Can a government-led project build the area up and out of crisis?

There is more than one way to raise a house.

Many of the mobile homes, Creole cottages, and other dwellings that have been flagged for flood risk along Louisiana’s low-lying coastline can be separated from their foundations and slowly raised into the sky on hydraulic jacks. While a home is held aloft by temporary support beams, a new, elevated floor is built underneath or the foundation extended upward—think of the pilings you might see supporting a beach house.

But for homes like Christa and Alex Bell’s, which consists of two stories and a two-car garage sitting on a concrete slab, the house-jacking process is more complex.

Slab homes depend on the concrete foundation underneath for flooring and for most, if not all, of their structural support. It’s ideal, though difficult, to raise the house and the slab together and build a new foundation underneath; the other option is to separate the two and build a new, elevated floor. From there, homeowners could extend the foundation walls up and construct a new bottom space they could use for storage or parking. Or they could remove the roof, raise the exterior walls up an entire story, replace the roof, and write off the house’s bottom floor as storage space.

No matter the approach, residents usually need to relocate for 60 to 90 days, after which their homes stand several feet higher in the air.

None of these details were on the Bells’ minds a decade ago when they moved from Alabama to Lake Charles, an oil refinery and casino town of 81,000 near the Gulf Coast and Texas border.

But in May 2021, more than a foot of rain came down on the region in just 24 hours, causing flash floods. Even as Christa Bell watched Bayou Contraband—one of the region’s many small, slow-moving rivers—rise until it spilled over and into their backyard, she wasn’t concerned her house might flood. Only a single corner of the 1,900-square-foot home was in a floodplain, according to federal flood maps when they bought the house in 2017. Yet that day, the bayou kept rising, and by evening, floodwaters stood shin deep in the living room. “Everything in the garage was just floating,” she says.

Every home on the block required at least partial gutting. Weeks passed; couches, mattresses, carpet, and other flood debris collected in heaps near the street, mildewed and rotting.

It was a scene mirrored across much of southwest Louisiana, and not for the first time. In a 10-month span in 2020–2021, the area saw five climate-related disasters, including two destructive hurricanes and the impacts of a tropical storm’s outer bands. More storms are coming, and many areas are not prepared: a 2021 study from First Street Foundation, a nonprofit focused on climate risk data, estimates that nearly 40% of Lake Charles residential properties and more than half the city’s infrastructure are at risk of future flooding.

Some people aren’t waiting around to experience that uncertain future. In the months after the 2020 hurricanes, Christa Bell says, she noticed more friends making home improvements before placing their houses on the market. “We had five disasters in a row. That hastened the departure for a lot of people,” she says. “If it flooded again, we would seriously think about it.”

But some government officials and state engineers are hoping there is an alternative: elevation. The $6.8 billion Southwest Coastal Louisiana Project is betting that raising residences by an average of three to five feet and nonresidential buildings by three to six, coupled with extensive work to restore coastal boundary lands, will keep Louisianans in their communities and a local economy that helps power the country’s oil industry running. The project, a collaboration between the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), is focused on roughly 4,700 square miles of land inthree parishes in the southwestern corner of the state: Cameron, Vermilion, and Calcasieu, where Lake Charles is the parish seat. More than 3,000 homes have been identified as being at risk of imminent flooding, and therefore as candidates for elevation funding.

Ultimately, it’s something of a last-ditch effort to preserve this slice of coastline, even as some locals pick up and move inland and as formal plans for managed retreat—or government funding for community relocation—become more popular in climate-vulnerable areas across the country and the rest of the world.

Since 1932, Louisiana has lost some 1.2 million acres of coast to erosion—an area nearly twice the size of Rhode Island.

Now, after eight years of surveys, paperwork, and waiting for cash, the pilot phase of the project is finally moving forward and raising 21 homes. As it does so, project staff and locals alike will be forced to grapple with a looming existential question: Can a region facing some of the nation’s most alarming climate predictions build its way out of an accelerating crisis?

Darrel Broussard, the project’s senior manager, sees its work as the region’s best chance at reducing damage over the next 50 years and safeguarding the roots residents have put down over generations. “This is Louisiana. This is where everyone lives. This is where we work. This is where the economy comes from,” he says. “There are models out there trying to predict the future. They’re just models. Right now, we currently have communities, neighbors, all living there.”

At the same time, some environmental experts worry that this may be too rosy an outlook, with time and nature conspiring against lasting success. “The sooner we can shift our mindset towards managed retreat, the better,” says Torbjörn Törnqvist, a geology professor at Tulane University. “This is a very tough issue. This is a part of the country that’s just going to disappear.”

It didn’t take long for the Bells to feel at home in Lake Charles, the biggest city in what Louisiana officials call the state’s “working coastline.” The economy here thrives on commercial fishing and agriculture, though petroleum services have long been at its heart; roughly 30% of Louisiana’s refining capacity is based in the region, and the state accounts for nearly one-sixth of the country’s refining capacity, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

But what appealed most to Christa Bell, a public relations professor at McNeese State University, was locals’ hospitality and cuisine—proud reflections of Louisiana’s friendly charm. She loved the warm aesthetic of historic Ryan Street’s red brick buildings, which stand in stark contrast to the city’s casinos and refineries and its single skyscraper, the former Capital One Tower.

The building has sat vacant since a hurricane damaged it nearly four years ago—and over that time it has become a symbol of the strain created by severe weather in an area where waterways flow like veins and where flooding occurs often.

When Congress first authorized the Southwest Coastal Louisiana Project in 2016, local and federal officials celebrated it as a step toward shoring up the region’s resiliency after catastrophic storms like 2005’s Hurricane Rita: $5.2 billion would go toward shoreline and marshland restoration, while $1.6 billion would elevate local structures to heights based on 100-year-flood levels predicted for 2075. (These levels are both a complex idea and a moving target. They refer to the type of flooding that has a 1-in-100 or 1% chance of happening in any given year, but what was considered a 100-year flood even a decade ago now occurs much more frequently, and the storms are more severe.)

The Corps completed a feasibility study that identified 3,462 homes and about 500 nonresidential structures and warehouses eligible for elevation. To meet the feasibility study’s criteria, houses had to be in the current 25-year floodplain (meaning there’s a 1-in-25 chance the property will flood in a given year)—a stipulation the agency says offers the “greatest rate of return.” For final inclusion in the project, homes will need to be able to structurally withstand the elevation process. They must also be free of hazardous materials like asbestos and have clear property titles. All structures will need to meet state and local building codes.

But with the federal government on the hook to cover 65% of project costs, work was effectively on hold until 2022, when Congress finally approved the first round of funding for building and land restoration: nearly $300 million through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. (The remaining 35% will come mostly through Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan—a 50-year, $50 billion guide to coastal restoration and storm risk reduction that’s updated every four years—and its funding allocated by the state.)

The Southwest Coastal Louisiana Project’s pilot program has been able to move forward on an initial round of agreements with 21 homeowners, though this batch of funding will ultimately cover 800 to 1,000 elevations over the next three to five years. Priority is being given to homes “that would flood the most,” Broussard says, meaning those with the lowest first floors, as well as houses in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. Officials estimate that each residential elevation will cost between $100,000 and $200,000; homeowners will pay nearly nothing out of pocket for the elevation but will cover any costs to make their homes eligible and for temporary housing during construction. (Relocation expenses for renters are covered under the federal Uniform Relocation Act.)

“Our benefits come from getting structures out of the floodplain, and the damage is avoided,” Broussard says. Once homes are elevated above 100-year-flood levels, “we shouldn’t have to touch them for at least 50 years.”

But some experts remain skeptical of this kind of certainty, particularly since the way we measure 100-year floods is changing as the climate warms. As recent research from First Street notes, such flood estimates are typically based on outdated data that do not reflect current rainfall or rising temperatures, among other factors. After adjusting the data to reflect a hotter, more humid atmosphere, its researchers estimate that a majority of Americans will experience what was previously considered a 100-year event every 20 years.

Törnqvist warns that the 100-year-flood predictions underpinning the project are essentially a gamble—and as in gambling, odds can change.

But it’s a bet coastal officials say they are willing to take.

While the project’s flood-risk modeling was conducted in 2016, Broussard says it considered future factors like increasingly powerful storms and sea-level rise. Since then, Broussard contends, “nothing has changed,” adding that the Corps does not intend to update models of future storm risk “at this time.”

But even under its most optimistic estimates, the project won’t finish raising structures until the early 2040s. By that time, decades will have passed since the project made the flood-level predictions that provide its foundation.

Raising homes won’t mean much in the long term if the project can’t preserve or rebuild land that has long acted as a natural barrier and protector for the coast’s residents. Broussard says the entire effort is like a complicated, very large puzzle: for one piece to fit, the correct piece must come before it; to protect inland Louisiana communities, you must protect the coast first. Without intervention, the state could spend up to $15 billion in disaster damage annually by midcentury, according to the CPRA.

Bren Haase, the CPRA’s chair and former executive director, says that “the landscape, the beaches, the cheniers, the ridges, and the vast areas of marshes are the protection for that portion of the coast” near Lake Charles. The marshlands have been particularly important in absorbing or temporarily storing excess storm surges, while cheniers—the coastal ridges running parallel to the gulf’s shoreline—have acted as natural levees, slowing down those same storm surges and providing a home to holly oak trees whose roots kept shorelines intact.

But since 1932, Louisiana has lost some 1.2 million acres of coast to erosion—an area nearly twice the size of Rhode Island. State officials estimate that parts of southwest Louisiana lose up to 30 feet of coast each year. Altogether, by 2050, Louisiana could see some 500,000 acres of additional land loss.

The CPRA estimates that Cameron Parish—most of which is wetlands—would be hit hardest among the coastal parishes, with up to 40% of its existing land likely to disappear by 2050. Without its marshlands, local flood depths could increase more than 15 feet.

“In the future, [Cameron Parish] is not going to be there,” Törnqvist says. “It’s going to be one of the first larger parish-level areas in Louisiana to go.”

Part of the problem is sea-level rise; another is an increase in the sheer amount of rain hitting the region. A significant contributor, though, is human activity, counterintuitively including past flood-control practices, like constructing dams upriver and levees to control the state’s numerous waterways. In southeast Louisiana’s Mississippi River Basin, a recent Nature Sustainability study estimates, the installation of these types of structures has led to a loss of roughly 1,700 acres annually. Then there was the dredging of transportation channels for the oil and gas industry, which redirected the plain’s primary sediment sources away from its marshland and allowed the land to disintegrate. Jetty systems have meanwhile disrupted sediment patterns that built the chenier ridges over about 7,000 years. Such activity has also allowed salt water to flow inland, which has in turn killed freshwater wetlands where roots held the soil together.

In this context, elevating local structures is the easy part of the project. It will be much harder to undo a century of damage to coastal buffers that required millennia to develop.

The Southwest Coastal Project is planning to move millions of tons of dredged mud, rocks, oyster shells, and other materials to replace eroded land or guard vulnerable shoreline. More than 5 million cubic yards of dredged sediment from the Calcasieu Ship Channel, for instance, will be used to convert about 600 acres of open water near Calcasieu Parish’s Black Lake back into marshland that had been lost to erosion. Meanwhile, more than 860,000 tons of rock will be strategically piled across a nearly nine-mile stretch that will extend existing breakwaters—artificial reefs that can reduce the impact of waves and lessen coastal erosion—at Cameron Parish’s Holly Beach.

In total, the project aims to preserve nearly 22,000 net acres through ecosystem restoration.

Fortunately, it won’t be working in isolation. Beyond Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan, various other CPRA schemes in Cameron Parish have already protected more than seven miles of shoreline and restored more than 3,800 acres of marsh, building more than 159,000 linear feet of earthen terraces to reduce wave erosion.

Still, officials like Haase are clear that future land loss is inevitable: “Even with our best and most aggressive efforts, the coast is going to continue to change.”

For all this to work, a lot needs to go right, and go right quickly.

Unfortunately, the pilot program is already behind initial time estimates: after funding was allocated, the Corps said it hoped the first structures would be elevated by early 2023. Nothing has yet been elevated. (The Corps says that “determining structure eligibility” and making multiple assessments at every location “has taken longer than expected.”)

Meanwhile, state support may also be at risk since a new Republican governor—former state attorney general Jeff Landry—has taken over from Democrat John Bel Edwards. Landry called climate change a hoax in 2017, and weeks after his January inauguration he issued an executive order calling for the potential merger of the CPRA and the state’s Department of Energy and Natural Resources, meaning the agency permitting petroleum industries would also oversee efforts to remediate their environmental fallout. (The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

While plans drag, storm systems will inevitably keep roaring ashore, and sea levels will continue to rise. Someday, homes elevated four to five feet above their current level won’t really be safe. And no matter how high homes go, cities like Lake Charles will still require local infrastructure upgrades, like bridges and sewer systems, that constitute a whole other set of vulnerabilities for residents. On top of that, storm winds have the power to cause severe structural damage, especially for homes at higher elevations; in 2020, Hurricane Laura’s wind speeds peaked at about 150 miles per hour.

Craig Colten, a former Louisiana State University geography professor and a community researcher, is similarly skeptical of the Southwest Coastal Project’s long-term success. “This notion that you can restore the coast—that might have been an ambitious and worthwhile goal in the 1990s, when people first started talking about it,” he says. “But now, as we’re seeing how this is playing out and realities of the pace of sea-level rise, I think most of the science community is saying maybe the restoration plan isn’t going to really rebuild the coast.”

Across the gulf, experts like Jim Blackburn, a professor of environmental law at Rice University in Houston, are calling for managed retreat instead. “Our mindset is wrong,” he says. “We’re more concerned about selling houses than telling the truth.”

Indeed, managed retreat is a strategy that is being applied globally, notes Jim Elliott, a Rice University sociologist researching natural disasters’ long-term community impacts. The option has been deployed in every US state and about 500 municipalities nationwide, he says.

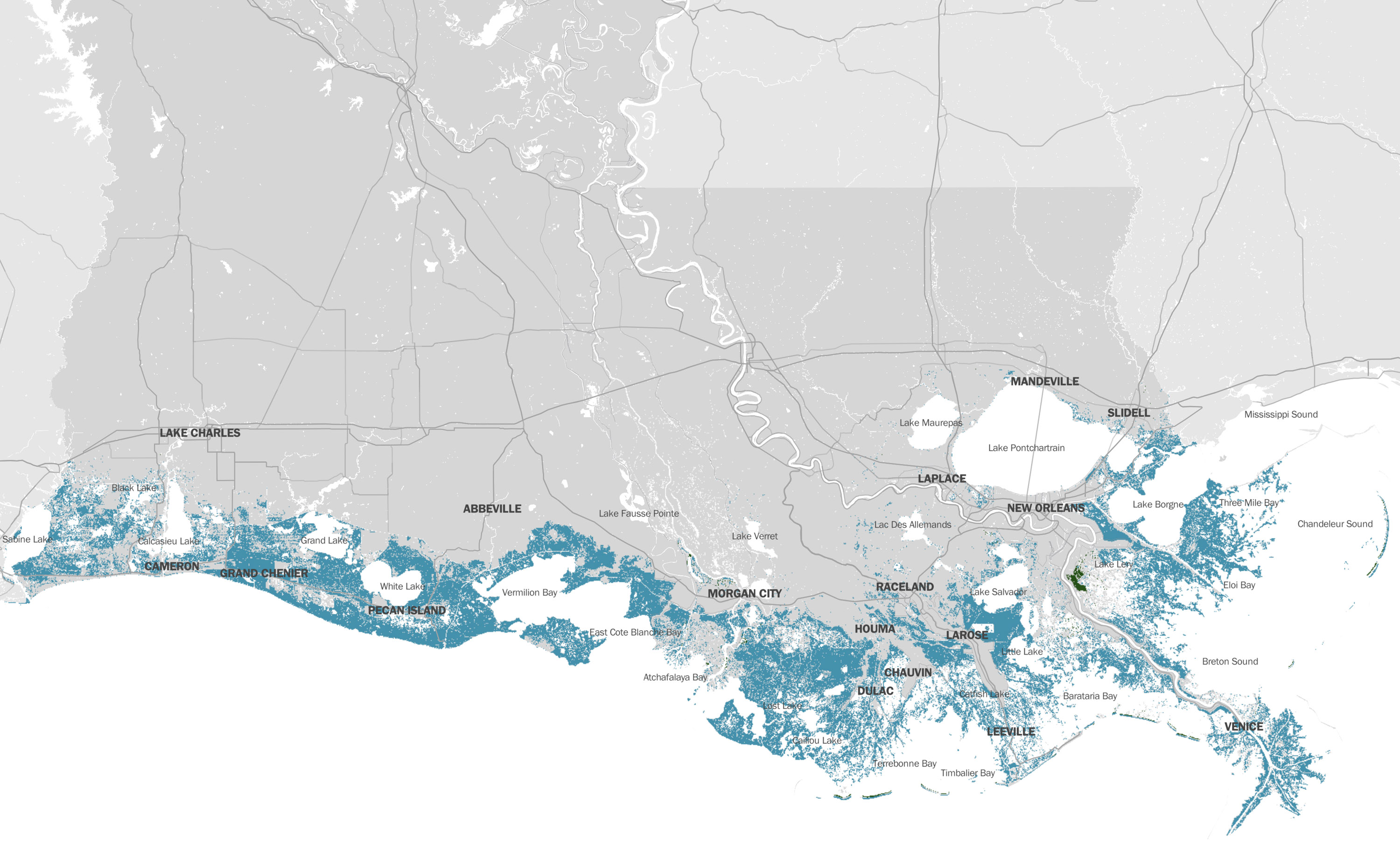

Continuing coastal change, sea-level rise, and other environmental processes will lead to additional land loss (shown in blue) in coastal Louisiana over 50 years. Projects included in the 2023 Coastal Master Plan attempt to mitigate this loss.

Yet Elliott explains that only small communities (like the Oakwood Beach neighborhood of Staten Island, New York, which was severely damaged during Hurricane Sandy in 2012) and communities already disappearing as a result of coastal erosion (like Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, and Newtok, Alaska) have seen success in acquiring mixtures of state and federal funding to relocate most of their households.

The effort to move the mostly Indigenous residents from Isle de Jean Charles is in fact the only time Louisiana has funded large-scale community relocation. By 2016, when state legislators allocated that funding, the rural island had lost almost 98% of its land and was barely habitable. Colten, who helped advise the state on the relocation process, called it “incredibly complex”; issues included disagreements among residents and construction delays on a new planned community off island. The price tag was also staggering: roughly $1 million was spent to relocate each household, for a total of about $45 million to move 40 families.

“The costs are absolutely frightening for government officials to think about,” he says. “Although the state very clearly touted the Isle de Jean Charles relocation as a model for guiding other relocation efforts, I don’t think that position is going to be made in the future.”

For these reasons, Colten believes, the government will attempt to avoid managed retreat until it’s the only option remaining, and only for those who can’t afford to relocate on their own.

Jennifer Cobian, Calcasieu Parish’s grants coordinator and assistant director of planning and development, says her parish has considered only small-scale managed retreat measures, like buyouts for individual homes in the city’s most flood-prone areas.

A buyout “is always a painful thought to have—that this whole area right here should be abandoned, or folks should move elsewhere,” Cobian says. Instead of “just abandoning properties or letting the property value go down,” she hopes the Southwest Coastal Project will “elevate them and [allow] the individual to stay in their home.”

Through those means, she believes, the community and economy can stay “vibrant, thriving.”

Cobian’s vision feels far off for locals like Sheila Ramsey, who has lived in Lake Charles her entire life. The only time she, her granddaughter, and her son, who uses a wheelchair, have lived elsewhere was after the 2020 hurricanes damaged their home and forced them to temporarily relocate.

When Ramsey and her family eventually returned to Lake Charles, they learned their home insurance company had declared bankruptcy; the policy she had paid into was null and void. Without that assistance, Ramsey has not been able to repair their home to livability. She also couldn’t afford to move, even if she wanted to. So she’s forced to choose between paying her monthly mortgage and fixing the house. The family lives in a rented camper on the front lawn.

“I’m just praying and believing to God that something’s gonna come through,” Ramsey says.

Stories like hers reflect the severe challenges facing southwest Louisiana. But while she and her family are essentially stuck waiting for help, others are leaving the area for good.

Migrating away from coastal threats is not exactly a new phenomenon in the region. Small-scale inland migration, or “moving up the bayou,” in some ways defines its history of survival, Colten says: “You stay within reach of your relatives and occupation by moving five, 10 miles up the bayou. It moves you out of harm’s way but keeps you in your cultural milieu.”

But movement over the past several years has been vastly accelerated. Since Hurricane Rita’s 18 feet of storm surge in 2005, Cameron Parish’s rural population has dwindled from roughly 10,000 to just about 5,000 today. And after the 2020 hurricanes, Lake Charles experienced the nation’s largest population exodus that year, according to US Postal Service change-of-address data.

Virginia Hanusik is an award-winning artist, author, and environmental advocate based in New Orleans, Louisiana. The photographs accompanying this story are part of an ongoing series exploring the relationship between landscape, culture, and the built environment. Her book Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana is available from Columbia University Press.

This makes life even more difficult for the people who stay, Colten says. Communities are “losing their ability to support the basic parish services and pay the personnel who need to be there to administer emergency management and basic fire and police services—the basics.”

Despite these challenges and the skepticism from experts, local officials like Calcasieu Parish’s Cobian and Haase, the CPRA chair, remain hopeful they have found a way build a future here.

Haase believes “with all [his] heart and mind” in southwest Louisiana’s survival. CPRA’s mission is “to provide for a sustainable coast into the future,” he says. “It’s not to provide necessarily for the same coast we have today, or the coast that we had 10 or 20 or 100 years ago, but it is to provide a sustainable footprint that’s livable.”

Christa Bell, meanwhile, is unsure if her family will stay or leave. She understands that elevating their home could be complicated, and she and her husband haven’t yet been contacted about the possibility. But if someone did reach out, she says, “we’d be willing to discuss if they could convince us they could do it without destroying the house, or costing an arm and a leg.”

Anything to avoid flooding, she adds. Even if that means leaving southwest Louisiana altogether.

Xander Peters is a writer living in his native east Texas. He’s a 2023 environmental-justice journalism fellow at Wake Forest University and a 2023 energy journalism fellow at Columbia University. His work has appeared in National Geographic, the Christian Science Monitor, Texas Monthly, and other publications.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

This classic game is taking on climate change

What the New Energies edition of Catan says about climate technology today.

How battery-swap networks are preventing emergency blackouts

When an earthquake rocked Taiwan, hundreds of Gogoro’s battery-swap stations automatically stopped drawing electricity to stabilize the grid.

The world’s on the verge of a carbon storage boom

Hundreds of looming projects will force communities to weigh the climate claims and environmental risks of capturing, moving, and storing carbon dioxide.

The cost of building the perfect wave

The growing business of surf pools wants to bring the ocean experience inland. But with many planned for areas facing water scarcity, who bears the cost?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.