Scientists are trying to get cows pregnant with synthetic embryos

Can animals be made without sperm or eggs? The answer could upend our ideas about what life is.

It was a cool morning at the beef teaching unit in Gainesville, Florida, and cow number #307 was bucking in her metal cradle as the arm of a student perched on a stool disappeared into her cervix. The arm held a squirt bottle of water.

Seven other animals stood nearby behind a railing; it would be their turn next to get their uterus flushed out. As soon as the contents of #307’s womb spilled into a bucket, a worker rushed it to a small laboratory set up under the barn’s corrugated gables.

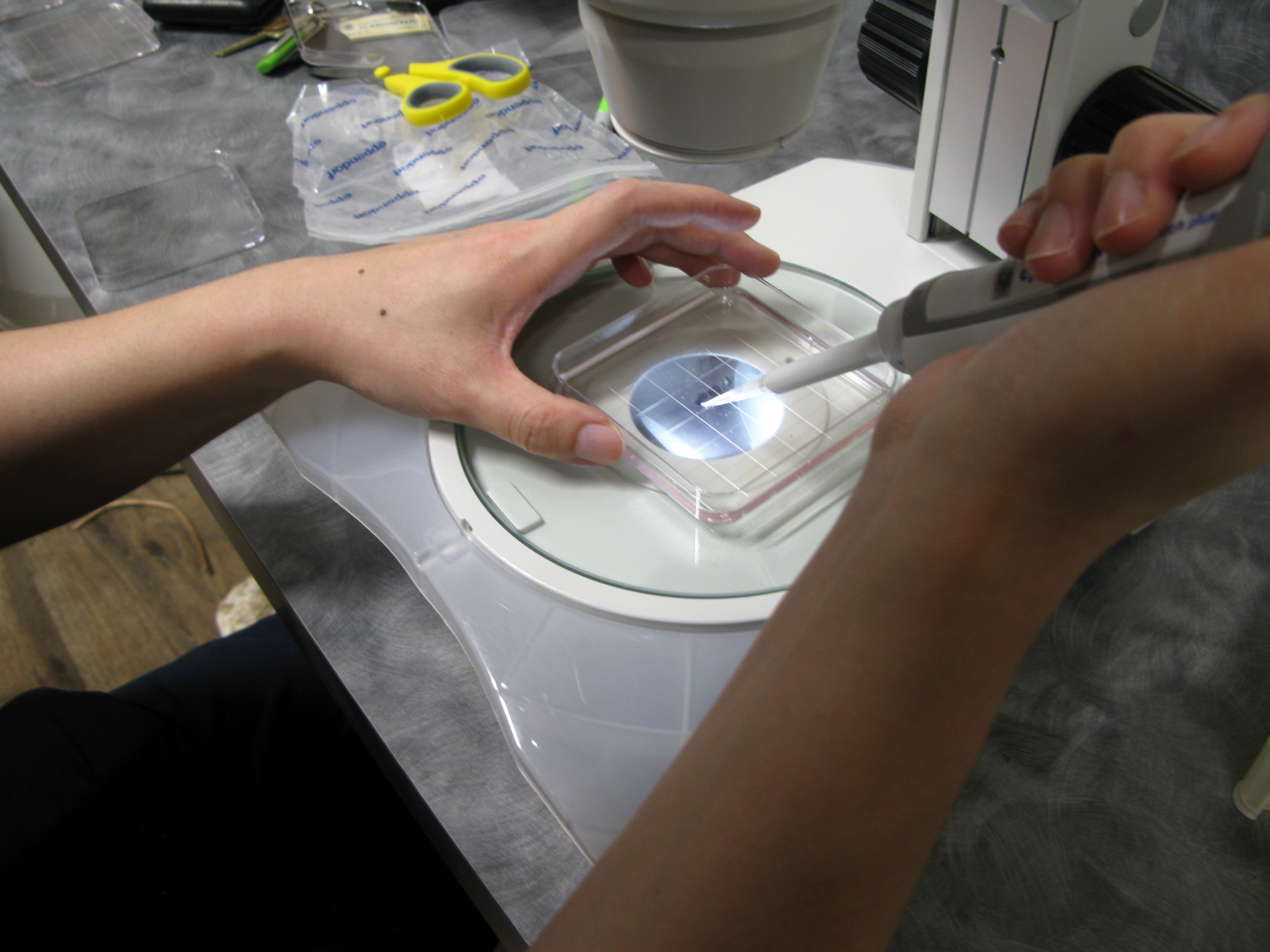

“It’s something!” said a postdoc named Hao Ming, dressed in blue overalls and muck boots, corralling a pink wisp of tissue under the lens of a microscope. But then he stepped back, not as sure. “It’s hard to tell.”

The experiment, at the University of Florida, is an attempt to create a large animal starting only from stem cells—no egg, no sperm, and no conception. A week earlier, “synthetic embryos,” artificial structures created in a lab, had been transferred to the uteruses of all eight cows. Now it was time to see what had grown.

About a decade ago, biologists started to observe that stem cells, left alone in a walled plastic container, will spontaneously self-assemble and try to make an embryo. These structures, sometimes called “embryo models” or embryoids, have gradually become increasingly realistic. In 2022, a lab in Israel grew the mouse version in a jar until cranial folds and a beating heart appeared.

At the Florida center, researchers are now attempting to go all the way. They want to make a live animal. If they do, it wouldn’t just be a totally new way to breed cattle. It could shake our notion of what life even is. “There has never been a birth without an egg,” says Zongliang “Carl” Jiang, the reproductive biologist heading the project. “Everyone says it is so cool, so important, but show me more data—show me it can go into a pregnancy. So that is our goal.”

For now, success isn’t certain, mostly because lab-made embryos generated from stem cells still aren’t exactly like the real thing. They’re more like an embryo seen through a fun-house mirror; the right parts, but in the wrong proportions. That’s why these are being flushed out after just a week—so the researchers can check how far they’ve grown and to learn how to make better ones.

“The stem cells are so smart they know what their fate is,” says Jiang. “But they also need help.”

So far, most research on synthetic embryos has involved mouse or human cells, and it’s stayed in the lab. But last year Jiang, along with researchers in Texas, published a recipe for making a bovine version, which they called “cattle blastoids” for their resemblance to blastocysts, the stage of the embryo suitable for IVF procedures.

Some researchers think that stem-cell animals could be as big a deal as Dolly the sheep, whose birth in 1996 brought cloning technology to barnyards. Cloning, in which an adult cell is placed in an egg, has allowed scientists to copy mice, cattle, pet dogs, and even polo ponies. The players on one Argentine team all ride clones of the same champion mare, named Dolfina.

Synthetic embryos are clones, too—of the starting cells you grow them from. But they’re made without the need for eggs and can be created in far larger numbers—in theory, by the tens of thousands. And that’s what could revolutionize cattle breeding. Imagine that each year’s calves were all copies of the most muscled steer in the world, perfectly designed to turn grass into steak.

“I would love to see this become cloning 2.0,” says Carlos Pinzón-Arteaga, the veterinarian who spearheaded the laboratory work in Texas. “It’s like Star Wars with cows.”

Endangered species

Industry has started to circle around. A company called Genus PLC, which specializes in assisted reproduction of “genetically superior” pigs and cattle, has begun buying patents on synthetic embryos. This year it started funding Jiang’s lab to support his effort, locking up a commercial option to any discoveries he might make.

Zoos are interested too. With many endangered animals, assisted reproduction is difficult. And with recently extinct ones, it’s impossible. All that remains is some tissue in a freezer. But this technology could, theoretically, blow life back into these specimens—turning them into embryos, which could be brought to term in a surrogate of a sister species.

But there’s an even bigger—and stranger—reason to pay attention to Jiang’s effort to make a calf: several labs are creating super-realistic synthetic human embryos as well. It’s an ethically charged arena, particularly given recent changes in US abortion laws. Although these human embryoids are considered nonviable—mere “models” that are fair-game for research—all that could all change quickly if the Florida project succeeds.

“If it can work in an animal, it can work in a human,” says Pinzón-Arteaga, who is now working at Harvard Medical School. “And that’s the Black Mirror episode.”

Industrial embryos

Three weeks before cow #307 stood in the dock, she and seven other heifers had been given stimulating hormones, to trick their bodies into thinking they were pregnant. After that, Jiang’s students had loaded blastoids into a straw they used like a popgun to shoot them towards each animal’s oviducts.

Many researchers think that if a stem-cell animal is born, the first one is likely to be a mouse. Mice are cheap to work with and reproduce fast. And one team has already grown a synthetic mouse embryo for eight days in an artificial womb—a big step, since a mouse pregnancy lasts only three weeks.

But bovines may not be far behind. There’s a large assisted-reproduction industry in cattle, with more than a million IVF attempts a year, half of them in North America. Many other beef and dairy cattle are artificially inseminated with semen from top-rated bulls. “Cattle is harder,” says Jiang. “But we have all the technology.”

The thing that came out of cow #307 turned out to be damaged, just a fragment. But later that day, in Jiang’s main laboratory, students were speed-walking across the linoleum holding something in a petri dish. They’d retrieved intact embryonic structures from some of the other cows. These looked long and stringy, like worms, or the skin shed by a miniature snake.

That’s precisely what a two-week-old cattle embryo should look like. But the outer appearance is deceiving, Jiang says. After staining chemicals are added, the specimens are put under a microscope. Then the disorder inside them is apparent. These “elongated structures,” as Jiang calls them, have the right parts—cells of the embryonic disc and placenta—but nothing is in quite the right place.

“I wouldn’t call them embryos yet, because we still can’t say if they are healthy or not,” he says. “Those lineages are there, but they are disorganized.”

Cloning 2.0

Jiang demonstrated how the blastoids are grown in a plastic plate in his lab. First, his students deposit stem cells into narrow tubes. In confinement, the cells begin communicating and very quickly start trying to form a blastoid. “We can generate hundreds of thousands of blastoids. So it’s an industrial process,” he says. “It’s really simple.”

That scalability is what could make blastoids a powerful replacement for cloning technology. Cattle cloning is still a tricky process, which only skilled technicians can manage, and it requires eggs, too, which come from slaughterhouses. But unlike blastoids, cloning is well established and actually works, says Cody Kime, R&D director at Trans Ova Genetics, in Sioux Center, Iowa. Each year, his company clones thousands of pigs as well as hundreds of prize-winning cattle.

“A lot of people would like to see a way to amplify the very best animals as easily as you can,” Kime says. “But blastoids aren’t functional yet. The gene expression is aberrant to the point of total failure. The embryos look blurry, like someone sculpted them out of oatmeal or Play-Doh. It’s not the beautiful thing that you expect. The finer details are missing.”

This spring, Jiang learned that the US Department of Agriculture shared that skepticism, when they rejected his application for $650,000 in funding. “I got criticism: ‘Oh, this is not going to work.’ That this is high risk and low efficiency,” he says. “But to me, this would change the entire breeding program.”

One problem may be the starting cells. Jiang uses bovine embryonic stem cells—taken from cattle embryos. But these stem cells aren’t as quite as versatile as they need to be. For instance, to make the first cattle blastoids, the team in Texas had to add a second type of cell, one that can make a placenta.

What’s needed instead are specially prepared “naïve” cells that are better poised to form the entire conceptus—both the embryo and placenta. Jiang showed me a PowerPoint with a large grid of different growth factors and lab conditions he is testing. Growing stem cells in different chemicals can shift the pattern of genes that are turned on. The latest batch of blastoids, he says, were made using a newer recipe and only needed to start with one type of cell.

Slaughterhouse

Jiang can’t say how long it will be before he makes a calf. His immediate goal is a pregnancy that lasts 30 days. If a synthetic embryo can grow that long, he thinks, it could go all the way, since “most pregnancy loss in cattle is in the first month.”

For a project to reinvent reproduction, Jiang’s budget isn’t particularly large, and he frets about the $2-a-day bill to feed each of his cows. During a tour of UFL’s animal science department, he opened the door to a slaughter room, a vaulted space with tracks and chains overhead, where a man in a slicker was running a hose. It smelled like freshly cleaned blood.

This is where cow #307 ended up. After a about 20 embryo transfers over three years, her cervix was worn out, and she came here. She was butchered, her meat wrapped and labeled, and sold to the public at market prices from a small shop at the front of the building. It’s important to everyone at the university that the research subjects aren’t wasted. “They are food,” says Jiang.

But there’s still a limit to how many cows he can use. He had 18 fresh heifers ready to join the experiment, but what if only 1% of embryos ever develop correctly? That would mean he’d need 100 surrogate mothers to see anything. It reminds Jiang of the first attempts at cloning: Dolly the sheep was one of 277 tries, and the others went nowhere. “How soon it happens may depend on industry. They have a lot of animals. It might take 30 years without them,” he says.

“It’s going to be hard,” agrees Peter Hansen, a distinguished professor in Jiang’s department. “But whoever does it first …” He lets the thought hang. “In vitro breeding is the next big thing.”

Human question

Cattle aren’t the only species in which researchers are checking the potential of synthetic embryos to keep developing into fetuses. Researchers in China have transplanted synthetic embryos into the wombs of monkeys several times. A report in 2023 found that the transplants caused hormonal signals of pregnancy, although no monkey fetus emerged.

Because monkeys are primates, like us, such experiments raise an obvious question. Will a lab somewhere try to transfer a synthetic embryo to a person? In many countries that would be illegal, and scientific groups say such an experiment should be strictly forbidden.

This summer, research leaders were alarmed by a media frenzy around reports of super-realistic models of human embryos that had been created in labs in the UK and Israel—some of which seemed to be nearly perfect mimics. To quell speculation, in June the International Society for Stem Cell Research, a powerful science and lobbying group, put out a statement declaring that the models “are not embryos” and “cannot and will not develop to the equivalent of postnatal stage humans.”

Some researchers worry that was a reckless thing to say. That’s because the statement would be disproved, biologically, as soon as any kind of stem-cell animal is born. And many top scientists expect that to happen. “I do think there is a pathway. Especially in mice, I think we will get there,” says Jun Wu, who leads the research group at UT Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas, that collaborated with Jiang. “The question is, if that happens, how will we handle a similar technology in humans?”

Jiang says he doesn’t think anyone is going to make a person from stem cells. And he’s certainly not interested in doing so. He’s just a cattle researcher at an animal science department. “Scientists belong to society, and we need to follow ethical guidelines. So we can’t do it. It’s not allowed,” he says. “But in large animals, we are allowed. We’re encouraged. And so we can make it happen.”

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

FDA advisors just said no to the use of MDMA as a therapy

The studies demonstrating MDMA’s efficacy against PTSD left experts with too many questions to greenlight the treatment.

Biotech companies are trying to make milk without cows

The bird flu crisis on dairy farms could boost interest in milk protein manufactured in microorganisms and plants.

Is this the end of animal testing?

Researchers are increasingly turning to organ-on-a-chip technology for drug testing and other applications.

What’s next for MDMA

The FDA is poised to approve the notorious party drug as a therapy. Here’s what it means, and where similar drugs stand in the US.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.